Key points

- Labour claims it found a £22bn “black hole” after taking power. Since then, both the Prime Minister and Chancellor have warned tough measures are needed to address it.

- The Tories dispute the claim and the financial markets appear to have ignored it.

- Those with “broad shoulders” are expected to face tax hikes, but there is no definition of how wealthy one must be to be considered “broad shouldered”.

- Regardless, a fall in spending coupled with increases in taxation – particularly against the very wealthy – can have unintended consequences. An unlikely outcome is growth – one of Labour’s stated goals.

- The Budget will not be held until 30 October and you should be wary of making changes prior to this date. Any such changes will be based on rumours rather than facts.

- Book a free initial meeting with one of our advisers to see if you are affected by any Budget change.

How much additional tax is needed

Within weeks of taking power, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rachel Reeves, claimed a £22bn black hole had been discovered in the public finances and said this hole needs to be filled.

Labour’s detractors highlighted the fact half of this sum (just over £11bn) was attributable to above-inflation public sector pay rises which were awarded by Labour, with Labour countering these rises were warranted to end to ongoing strike action.

The ex-Chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, also queried how these budget gaps could have been identified when senior civil servants had signed off on different figures shortly beforehand.

The financial markets appeared to shrug off any concerns about this “black hole”. The chart below shows government borrowing costs for the USA, UK, and Germany in the few days either side of Reeves’ announcement on 29 July.

UK government borrowing costs (shown in blue) actually fell on the day of the announcement, roughly in line with similar falls in the USA and Germany.

In contrast, the chart below shows the same three measures in the days surrounding Liz Truss’ infamous “mini budget” on 23 September 2022:

Here, the borrowing markets responded logically to a large government deficit: the UK borrowing cost rose dramatically, particularly when compared with other countries.

For completeness, it is worthwhile noting the scale of the two scenarios was entirely different (the mini budget contained over £100bn of unfunded tax cuts and spending). However, both scenarios relate to the announcement of an unfunded liability and yet one did not cause a spike in borrowing rates.

Nonetheless, Reeve’s “black hole” announcement set the scene for tax rises and public spending cuts.

Reeves proceeded to implement Labour’s election pledge to impose VAT on private school fees along with changes to the “non-dom” rules (special tax treatment for those who have moved to the UK but have assets/income elsewhere in the world).

Reeves also made the shock announcement that the winter fuel allowance would be immediately abolished for anyone not in receipt of a state benefit. The underlying aim of this change was to ensure pensioner millionaires do not continue to receive this tax-free government money.

These announcements gave some indication of how Labour defines “broad shoulders”: while the non-dom rule changes arguably only affect the very wealthy, many traditionally “middle class” families send their children to private schools. Cutting off a fuel allowance to huge numbers of people to stop it getting to a far smaller number of wealthy pensioners shows Reeves and Starmer are willing to make highly unpopular changes to raise more money.

How much tax are people willing to pay

Labour won with a clear majority of seats despite not pledging any tax cuts or spending rises. Arguably, the electorate knew it could expect to see some tax rises, as Labour was bound to fix issues it said were left by the previous government.

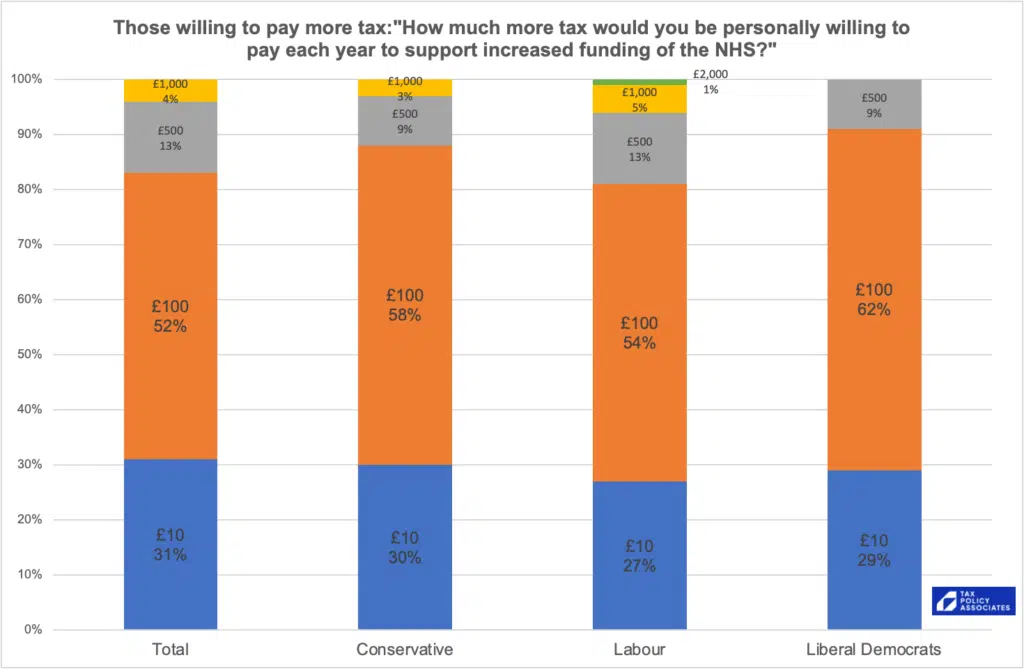

However, research by Tax Policy Associates carried out in March 2024 suggests there is a gulf between how much the government wants to raise vs how much people are willing to pay.

Source: Tax Policy Associates Public attitudes to paying more tax to fund the NHS

By way of context, there are around 36 million taxpayers in the UK. To raise an additional £10bn, each taxpayer would have to pay £278. The research quoted above suggests 83% of taxpayers would not pay more than £100, even if this was to specifically fund the NHS.

There is also the question of how much support any taxes rises might have. Labour won 63% of seats (411) but with only 34% of the vote, with its victory being seen as a sign of Tory fatigue rather than an endorsement of Labour’s manifesto pledges.

Where can the money be raised?

Labour tied one hand behind its back during its election campaign by repeatedly promising not to raise income tax, VAT, National Insurance Contributions, or Corporation Tax.

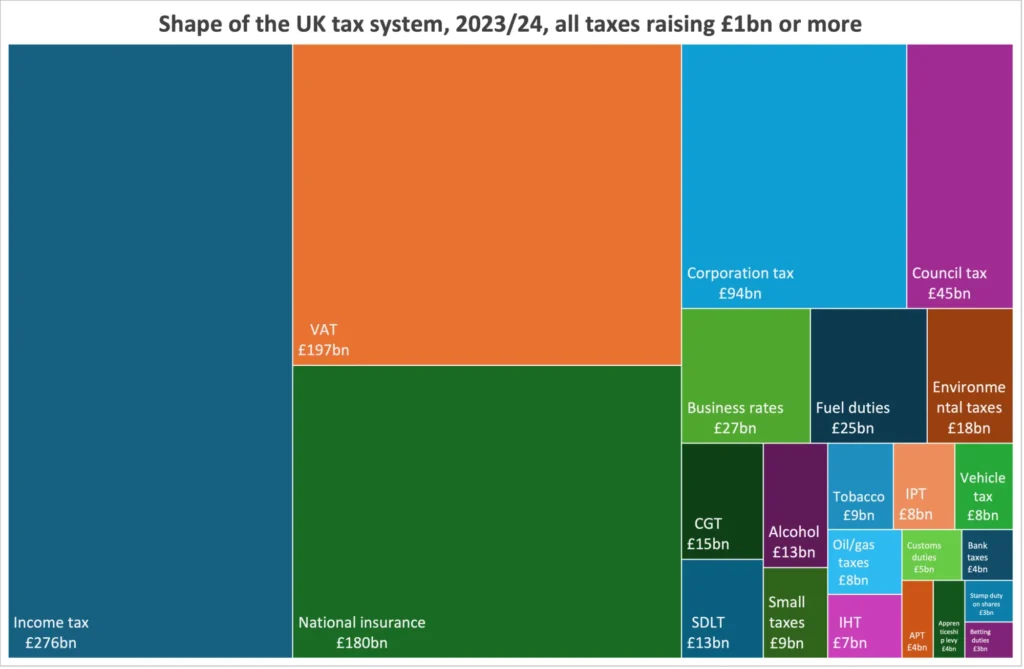

This diagram demonstrates how much money was taken off the table because of this decision:

Source: Tax Policy Associates How could Rachel Reeves raise £22bn of tax?

As you can see, Labour took the four biggest taxes out of the equation. This leaves just the small cluster in the bottom-right corner plus Council Tax to raise £22bn.

Some of the measures which could be implemented include:

Reduce tax relief on pension contributions

The vast majority of taxpayers currently get full income tax relief on pension contributions up to the lower of either £60,000 per year or their salary. By changing this to a flat rate of 20% or 30%, higher rate and additional rate taxpayers would lose out.

In our view, this would be an unfair. It would affect those earning around £50,000 or more, which is above the UK’s average wage but is obviously not the domain of the very wealthy.

We believe this change would be difficult to implement. For example, auto enrolment rules mean employers must pay 3% of an employee’s earnings into a pension plan. Presumably these employer contributions would not be caught by a removal of additional tax relief on pension contributions.

This could incentivise workers to give up part of their earnings in exchange for bigger employer pension contributions (a process known as salary exchange or salary sacrifice).

In addition, higher earners in schemes where contributions are taken from pre-tax pay (such as most public sector schemes) would face a tax bill each year, which would result in an additional burden for both HMRC and the taxpayers.

Related to this point, the previous government recognised the risk of senior NHS staff (such as GPs) leaving work due to the tax burden on larger pension savings. As a result, it brought in tax changes specifically to accommodate these savers.

If Labour caps pension contribution tax relief at 20% or 30%, it means senior NHS staff would face an added tax bill in exchange for remaining a member of the scheme, potentially leading to a further exodus of experience from the NHS. (Update – according to the Times, the government has now backed off the idea of removing tax relief for higher earners for this reason.)

Also, this change would remove an important incentive for savers. Pension savers tie up their money until retirement, which currently means until age 55 but which will rise to 57 or 58 in the future. The added tax relief for higher earners encourages these workers to plan for the future.

This is a change which would solely target workers. Pensioners and those not in work would not be affected at all. For context, page 21 of Labour’s manifesto stated “Labour will not increase taxes on working people…”

Even the super-wealthy would not be as affected as lower earners: the annual cap on tax-relieved pension contributions gradually reduces down to £10,000 (from £60,000) for those earning over £260,000 per year, meaning very high income earners tend not to use pension savings to reduce their tax burden.

Bring in a death tax on pension plans

Pension death benefits are a very complex topic but, in a nutshell, current rules allow those who die before age 75 to leave just over £1m tax-free, while the beneficiaries of those who die aged 75+ pay income tax on pension death benefits.

Regardless of age, pension death benefits are not normally included when considering inheritance tax.

The reason pension death benefits are normally not included in an inheritance tax calculation is because they are held on trust, with the pension trustees having total discretion over who should receive the death benefits.

Labour could, in theory, set aside this rule and make pension death benefits part of an inheritance tax calculation. This would be extremely unfair, as it would re-write history for pension savers.

There is also debate about whether (or how) public sector pensions would be included in such a change. If they are not included, someone leaving behind £50,000 in a personal pension plan could be subject to inheritance tax (depending on the value of their other assets), while a public sector worker leaving behind tens of thousands of pounds per year of guaranteed income payments would not be subject to inheritance tax.

Instead of changing Inheritance Tax rules regarding pension death benefits, Labour could change an allowance only recently brought in by the Tories. The Lump Sum and Death Benefits Allowance allows up to £1,073,100 to be left as tax-free lump sum to beneficiaries (although – as set out in the linked post – many pension plans will avoid this test anyway).

Labour could increase the number of events which are tested against this allowance and/or reduce the allowance itself.

However, this would also be widely considered unfair. The Lump Sum and Death Benefits allowance was brought in to replace parts of the Lifetime Allowance. This allowance was cut a number of times over the years in which it was in force but – each time a reduction occurred – protections were brought in to benefit some of those who had made historic pension savings on the basis of the larger allowance.

Additionally, as with a change to Inheritance Tax rules, such a change could leave public sector workers unaffected while private sector workers face tax on their pension death benefits.

Yet again, this raises the question of who has “broad shoulders”. Someone with a £500,000 pension fund might be considered relatively wealthy by the general public, while a public sector worker with a £25,000 annual pension would probably not fall into this category. Yet, for the purposes of several pension rules and calculations, a £25,000 annual pension is broadly equivalent to a £500,000 pension fund.

A widow/widower left with a £500,000 pension plan may have lost the sole breadwinner in the family and face a retirement with only one State Pension and none of their own retirement provision, so taking large sums of tax off the inherited monies could be very detrimental.

Removing Inheritance Tax reliefs

There have been longstanding reliefs against Inheritance Tax for certain assets such as some private limited company shares, agricultural land, and some publicly-listed company shares.

These reliefs were intended to encourage investment in these assets and to ensure they can be passed through generations without taxation causing disruption. Over the years, financial products were created which have the potential to qualify for these reliefs without someone starting their own business (or similar).

It has been rumoured these reliefs could be removed or reduced. In our view, this would be unfair. Investors risk their capital by holding these types of investments. These investments often involve companies which support carbon reduction (such as wind farms and solar farms). In terms of the relief on some smaller publicly-listed companies, offering Inheritance Tax relief provides an incentive to invest in an area which has become somewhat unloved in recent years.

Any removal or reduction in this incentive will no doubt cause some outflows. This appears at odds with Labour’s vow to cut carbon emissions and to increase investment in UK companies.

Increase Capital Gains Tax (CGT)

The previous government brought more and more people into paying CGT by gradually reducing the CGT allowance (properly known as the “Annual Exempt Amount”), which went from £12,000 per person, to £6,000, down to its current amount of £3,000 per person.

There is currently a link between income and Capital Gains: to find out the rate at which CGT will be paid, a taxpayer must add the gain to their other taxable income to determine how much falls under the basic rate band and how much falls above it.

The rates are then 10% (or 18% for property) for any gain within the basic rate band plus 20% (or 24% for property) for any gain above the basic rate band.

This process is explained in detail on the government website.

Labour (and the Lib Dems) previously mooted the idea of raising CGT rates in line with income tax rates – that is, 20% for gains within the basic rate band and 40% (or 45%) for gains above it.

There are also rumours that Entrepreneur’s Relief – a flat CGT rate of 10% for those selling a business – could be removed.

Opponents of a rise in the CGT rates point out there is no allowance for inflation when considering taxable gains. The cumulative effect of inflation over the last, say, 30 years means a pound has halved in value.

Put another way, an investment property bought in 1994 for £75,000 would need to be worth at least £150,000 now just to maintain its value for inflation purposes. This does not allow for any investment gain. Yet if it was sold under current rules, the £75,000 gain would be assessed for CGT.

Many view the current lower CGT rates as a form of compensation for the fact there is no allowance for inflation. But Labour may not share the same view when it is seeking to raise additional tax revenue.

It is also worthwhile bearing in mind the fact assets which are subject to CGT also tend to be subject to other taxes.

For example, many such assets produce an income and this income is already subject to income tax (e.g., dividends on shares, rent on property).

These assets could also form part of a taxable estate for Inheritance Tax purposes, meaning the gain will eventually be subject to 40% tax when the owner dies.

Finally, it must be considered what the reaction of business founders/entrepreneurs could be if an incentivisation to grow a UK business is removed. This behavioural reaction is explored in the next section.

Do tax rises work?

There are two points to discuss on this topic.

The first is the fact people faced with a tax rise are sometimes able to alter their behaviour to reduce their tax liability. Generally, the wealthier the taxpayer and/or the bigger the tax rise, the more behaviour will change.

For example, if pension contribution tax relief is changed – will savers accept this change, or will they significantly reduce their pension contributions, or will they spend the extra money, or will they pursue potentially riskier options which still provide income tax relief?

The bigger long term risk to the economy is economic migration out of the country. Very wealthy people tend to have interests in different countries and can quite easily “up sticks” whenever they wish. Talk of a gloomy economy coupled with tax hikes is likely to encourage these people to leave the UK – and take their money with them.

While most people like to see the richest pay their “fair share”, the fact is a relatively small number of very wealthy individuals already contribute large shares of tax revenue. If this disappears, it could lead to even more problems for the economy – ultimately the same tax burden spread across fewer, less wealthy people.

The second point relates to the “government multiplier” or “fiscal multiplier”.

It is a widely accepted concept that when a government spends £1 it will eventually contribute more than £1 to the economy. This is the government multiplier.

This does not mean the government has an unlimited money printing machine, but instead it means sensible government spending/investment plans can yield positive returns for an economy.

By raising taxes and/or cutting spending, Labour will detract government spending from the economy. In theory, this means the sum taken from the economy will be greater than the reduction in net government spending.

This would be a poor outcome for any government, but it appears a particularly odd decision for a campaign with the key goal of “growth”.

Our View

To date, there have been no leaks or official statements on what measures might be announced in the Budget. For this reason, it is not advisable to make significant financial changes in the meantime – any such changes would be based solely on rumours and conjecture.

We believe it is likely “middle class” taxpayers will be surprised to find they are on the receiving end of some form of tax increase resulting from the October Budget, simply because middle class taxpayers are numerous, relatively wealthy, and relatively easy to tax.

Ideally, we would like to see government policies based on increasing public sector productivity, planning long term national investments, and making relatively small (and palatable) changes to taxation policy over time, thereby allowing individuals and businesses to make their own long-term plans without worrying the rug could be pulled out from under them by a sudden shift in tax rates, tax allowances, or tax reliefs.

We can only hope this is what we will see in the October Budget.